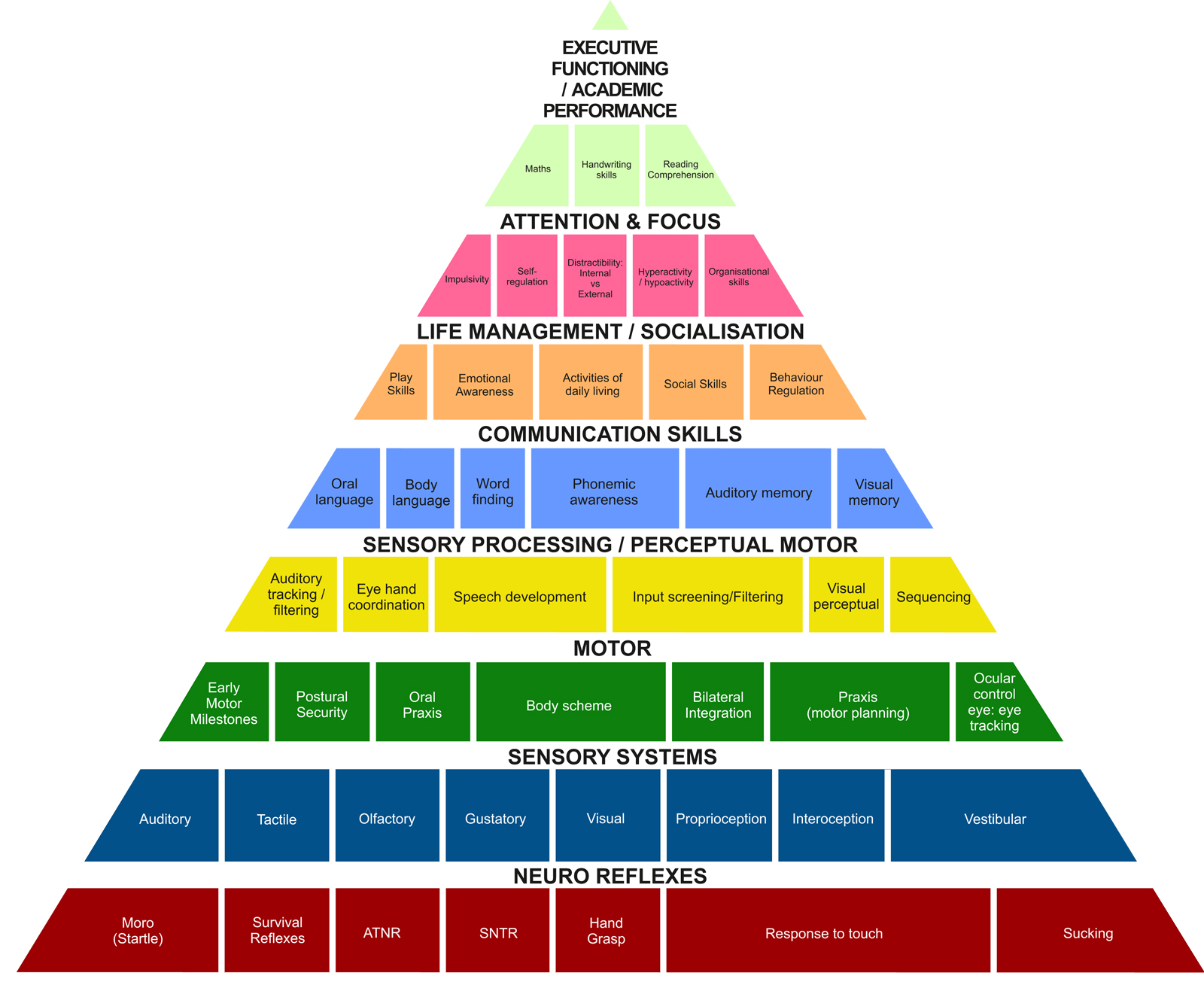

Developmental Pyramid

The Sensory Systems

Sight and Hearing are the senses that are commonly tested regularly starting at birth as they are the most obvious. These checks however only test the ‘kit’ and not how the information they give us is processed.

Neurological processing is a huge area of significant scientific research and study. The processing by an individual of the information gained from the environment through their senses is known as sensory processing.

Every one of us has our own sensory preferences and through life we’ve learned to live and adapt to what we like or don’t like, can or can’t do. Each one of us is hardwired neurologically to survive and protect ourselves and navigate day to day lives.

However, when one or more of our systems go offline, we do not function at our optimal levels thereby impacting on our performance.

In a child, if one or more of these systems is ‘stuck’ or delayed in its development, it can impact on various aspects of daily life, including, academic underperformance, self-esteem issues and create problems at home.

The vestibular system is a collection of structures in your inner ear: we have small, fluid filled canals, and the fluid in these canals moves every time we move our head. Receptors in these canals pick up the direction of movement and send this information on to our brain. So, we know if we are moving forwards, backwards, side to side, tilting our head, turning around or moving up and down (spatial orientation). This system also provides you with your sense of balance. Your brain then integrates that information with other sensory information from your body to coordinate smooth and well-timed body movements.

It is a complex series of actions and not something we’re born innately knowing to do. We all learned to walk as toddlers by honing and refining these interacting systems, and every time you learn something new that requires balance (like riding a bike, balance beam games in PE, skateboarding/snowboarding, or paddle boarding) your brain further modifies and refines these integration processes.

What many people don’t know is that the vestibular system is also responsible for:

- regulating muscle tone

- eye muscle control (tracking skills which allow you to read smoothly across a printed page, drop down to the next line without skipping lines and copy from the board)

- self-regulation which includes:

-focus and attention

-impulse control

-distractibility

-arousal level (hyperactive or hypoactive)

-organisational skills

Signs of difficulty with vestibular processing include:

- Dislike/fear or craving/seeking out activities requiring feet to leave the ground such as swings, slides, riding a bike, jumping or climbing.

- Clumsiness or frequent falling

- Often moving slowly/cautiously

- Frequent motion sickness/dizziness

- Appearing to never become dizzy with excessive spinning

- Seemingly unaware of danger/risks or impulsively jumping, running, and/or climbing

- Appearing frequently “lost” in their environment or having difficulty locating objects

- Dislike of being moved onto stomach or back as a baby or having their head tilted back

- Rocking, spinning, twirling, or frequent head tilting. May also intently watch moving objects

- Often prefers sedentary activities

- Difficulty sitting still or unable to sustain attention without moving

- Difficulty with reading, writing, and/or math

- Often slouches, holds head up with hands, or prefers lying down

Children that are noted to chew or suck on collars, sleeves, pencils, hair, etc are often telling you that their vestibular system is not doing its job, so they revert to a more primitive system (oral) to calm and focus themselves. Be careful not to remove the child’s compensatory technique until such time as the vestibular system has matured.

Proprioceptive System

Proprioception means “sense of position.” Its receptors are located within our muscles, joints, ligaments, tendons, and connective tissues. General proprioception describes the position of our body parts. Proprioception is the medical term that describes the ability to sense the orientation of your body in your environment. It allows you to move quickly and freely without having to consciously think about where your arms and legs are and where you are in your environment. Proprioception is a constant feedback loop within your nervous system, telling your brain what position you are in and what forces are acting upon your body at any given point in time.

The way that we can tell that an arm is raised above our head, even when our eyes are closed, is an example of proprioception. Other examples may include your ability to sense the surface you are standing upon, even when you are not looking at the surface. If you are walking along the sidewalk, and then turn to walk upon a grassy surface, your body knows how to adjust to the change in surface because of proprioception.

Difficulties with proprioception manifests itself as children who are clumsy, uncoordinated, and have difficulty performing basic normal childhood tasks and activities. Without proper messages regarding whether muscles are being stretched, whether joints are bending or straightening, and how much of each of these is happening, children will have the following “clinical” signs of proprioceptive dysfunction:

- difficulty “motor planning”; i.e. conceptualizing and figuring out what each part of his body needs to do in order to move a certain way or complete a task (what is an unconscious sense to us, becomes an active, conscious, frustrating sense to them)

- difficulty executing planned movements: i.e. “motor control” (the brain may know what to do, but they can’t figure out how to make their body do it)

- difficulty “grading movement”; knowing how much pressure is needed to complete a task (i.e. hold a cup of water, hold and write with a pencil, turn the page of a book, throw/kick a ball into the hole, etc.)

If children are under responsive to proprioceptive input (i.e. sensory seeking) they will:

- walk/run too hard (heavy-footed), push too hard, bang too hard write too hard, play with objects too hard, etc.

- be the loud ones, rough ones, crashers, movers, jumpers, runners, and bouncers (i.e. an insatiable bundle of energy!)

- shake his legs or constantly bang the back of his foot on the floor/chair while sitting in class

- play too rough (often hurting himself or others), jump off of or crash into anything he can, crack his knuckles, chew on his fingers, bite his nails until they bleed, chew on pens, gum, pencils, clothing collars, sleeves, or strings, or inedible objects (i.e. paper clips, pieces of toys etc.)

- enjoys tight clothes (i.e. turtlenecks, tight belts, hoods, hats, jackets zipped all the way up, tight pyjamas etc.)

- frequently bump into objects and people accidentally; trip and fall often

Oral Proprioception is the awareness of where your tongue, lips, teeth, and cheeks are, as well as the ability to manipulate those structures automatically and subconsciously for speech, sucking, drinking, and eating skills. Delayed oral praxis (oral motor planning), due to delayed proprioceptive feedback in a child’s mouth and oral cavity can have an impact on his speech production, articulation (mushy mouth), and ability to orally manipulate, suck, chew and swallow food appropriately, often resulting in ‘messy eating’.

Interoceptors are sensory receptors which receive stimuli from within the body, especially from the gut, bladder, and other internal organs. Very often children that have proprioceptive issues also have issues with bladder and bowel control. This function is supposed to be subconscious/automatic, however, they don’t ‘feel’ the stretch receptors until it’s too late or not at all.

Tactile System

We receive tactile information through sensory receptors located in the skin. The tactile system provides us with information about touch sensations: pressure, vibration, movement, temperature and pain. The tactile system involves the entire skin network including in the mouth, where tactile nerve endings are present in the cheek linings. Tactile input includes light touch, firm touch, and the discrimination of different textures from smooth to rough, hard to soft, etc..

Tactile sensitivity or hypersensitivity is an unusual or increased sensitivity to touch that makes the person feel peculiar, noxious, or even interpret touch as pain. It is also called tactile defensiveness or tactile over-sensitivity. Like other sensory processing issues, tactile sensitivity can run from mild to severe.

Children who have Tactile Over-responsivity (tactile defensiveness) are sensitive to touch sensations and can be easily overwhelmed by, and fearful of, ordinary daily experiences and activities.

Sensory Over-responsivity (sensory defensiveness) can prevent a child from play and interactions critical to learning and social interactions.

Often, children with Tactile Over-responsivity (tactile defensiveness) (hypersensitivity to touch/tactile input) will avoid touching, become fearful of, or bothered by the following:

- textured materials/items

- “messy” things

- vibrating toys, etc.

- a hug

- certain clothing textures

- rough or bumpy bed sheets

- seams on socks (Seamless Socks)

- tags on shirts

- light touch

- hands or face being dirty

- shoes and/or sandals

- wind blowing on bare skin

- bare feet touching grass or sand

- over-reaction to pain

The tactile system can also manifest immaturity by a child exhibiting ‘sensory-seeking’ behaviour. Here a child will touch everything and everyone he can, seeking touch-input in an attempt to mature his system.

Auditory System

The auditory system is the sensory system for the sense of hearing. It includes both the sensory organs (the ears) and the auditory parts of the sensory system. Auditory defensiveness is a discomfort, hypersensitivity, or an avoidance of certain sounds, which would not be particularly disturbing or distressing to most people.

Many children, who have sensory processing difficulties, suffer from auditory defensiveness. Hypersensitivities to sensory input may include:

- extreme response to or fear of sudden, high-pitched, loud, or metallic noises like flushing toilets, clanking silverware, hairdryers, vacuums, or other noises that seem unoffensive to others.

- Cinemas that play soundtracks too loud

- Reverberation in enclosed pool areas

Auditory processing disorder (APD), also known as central auditory processing disorder (CAPD), is a processing problem that affects about 5% of school-aged children. Kids with this condition can’t process what they hear in the same way other kids do because their ears and brain don’t fully coordinate input.

Your child passes a hearing test but is diagnosed with auditory processing disorder (APD). How is it possible to have an auditory disorder when you don’t have a hearing impairment?

Children with APD typically have normal hearing. But they struggle to process and make meaning of sounds. This is especially true when there are background noises.

Researchers don’t fully understand where things break down between what the ear hears and what the brain processes. But the result is clear: Kids with APD can have trouble making sense of what other people say.[1]

Typically, the brain processes sound seamlessly and almost instantly. Most people can quickly interpret what they hear with an appropriate reaction. However, with APD, some kind of glitch delays or “scrambles” that process. To a child with APD, “Tell me how the chair and the couch are alike” might sound like “Tell me how a cow and hair are like.”

Many conditions, including ADHD and autism, can affect a child’s ability to listen and understand what they hear. What makes APD different is that the problem lies with understanding the sounds of spoken language, not the meaning of what’s being said.

There are several kinds of auditory processing issues. The symptoms can range from mild to severe. Children with APD can have weaknesses in one, some or all these areas:

- Auditory discrimination: The ability to notice, compare and distinguish between distinct and separate sounds. The words seventy and seventeen may sound alike, for instance.

- Auditory figure-ground discrimination: The ability to focus on the important sounds in a noisy setting. It would be like sitting at a party and not being able to hear the person next to you because there’s so much background chatter.

- Auditory memory: The ability to recall what you’ve heard, either immediately or when you need it later.

- Auditory sequencing: The ability to understand and recall the order of sounds and words. A child might say or write “ephelant” instead of “elephant,” or hear the number 357 but write 735.

Children with APD usually have at least some of the following symptoms:

- Find it hard to follow spoken directions, especially multi-step instructions

- Ask speakers to repeat what they’ve said, or saying, “huh?” or “what?”

- Be easily distracted, especially by background noise or loud and sudden noises

- Have trouble with reading and spelling, which require the ability to process and interpret sounds

- Struggle with oral (word) math problems

- Find it hard to follow conversations

- Have poor musical ability

- Find it hard to learn songs or nursery rhymes

- Have trouble remembering details of what was read or heard

Visual Processing

Visual processing involves how the visual system takes in information, organizes it, and uses it to perform a functional task. A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer.

A child with visual problems may:

- Omit, substitute, repeat, or confuse similar words.

- Have difficulty with sizing, spacing, or copying written words.

- Confuse left/right directions.

- Have eye-hand coordination problems (e.g., shoe tying, buttons, participating in sports

activities).

Many times, children are misdiagnosed as having a ‘perceptual’ issue when in fact it is a motor accuracy issue. The eyes are seeing the designs, numbers, letters correctly, but the ability to direct the hand to draw what the eyes see is impaired (motor planning or motor accuracy issue). It is very important to assess where the difficulty actually lies.

A lot of children are misdiagnosed with Developmental Dyslexia, a perceptual issue, when in fact, as mentioned above, it is a motor accuracy issue. The treatment approaches are very different, so correct diagnosis is imperative.

Taste

Taste is a perception that results from stimulation of a gustatory nerve. Taste belongs to the chemical sensing system and begins when molecules stimulate special cells in the mouth or throat. These special cells transmit messages through nerves to the brain, where specific tastes are identified. Gustatory, or taste, cells react to food and beverages. The taste cells are clustered in the taste buds of the mouth and throat. Many of the small bumps that can be seen on the tongue contain taste buds. Smell contributes to the sense of taste, as does another chemosensory mechanism, called the common chemical sense. In this system, thousands of nerve endings, especially on the moist surfaces of the eyes, nose, mouth, and throat give rise to sensations such as the sting of ammonia, the coolness of menthol, and the irritation of chili peppers. People can commonly identify four basic taste sensations: sweet, sour, bitter, and salty. In the mouth, these tastes, along with texture, temperature, and the sensations from the common chemical sense, combine with odours to produce the perception of flavour. Flavours are recognised mainly through the sense of smell. If a person holds his or her nose while eating chocolate, for example, the person will have trouble identifying the chocolate flavour even though he or she can distinguish the food’s sweetness or bitterness. That is because the familiar flavour of chocolate is sensed largely by odour.

The most common signs of oral defensiveness include gagging and avoidance of strong-tasting foods. Depending on severity, this particular disorder is likely to affect an individual’s diet, making mealtime difficult/stressful and possibly leading to weight management difficulties.

If a child has oral dysfunction with hyposensitivity, he/she may often put things into the mouth that are inedible, also known as pica. Chewy tubes or chewy jewellery can help a child fulfil their desire for oral stimulation in a more appropriate manner, safe manner.

Olfactory

Olfactory perception is a process that starts in the nose with the stimulation of olfactory sensory neurons and terminates in higher cerebral centres which, when activated, make us consciously aware of an odor.

Olfactory defensiveness (smell) is an oversensitivity or overreaction to certain smells that are not generally considered aversive or noxious. An individual can be going throughout their day and a strong foul smell tells the brain to plug their nose, or a comforting, baking smell fills the house and someone instantly is in a better mood. Smell is linked to our memories, our emotions and our taste. For a child dealing with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD), smell sensitivities and defensiveness can feel very suffocating. A child who is hypersensitive to smells is overwhelmed by the onslaught of odours and scents from all directions. Other children and teachers often do not notice the scents that are bothering someone who is sensitive to smells. One of the most common complaints is from a child who can’t concentrate on their school work because all they can focus on is the smell of cleaning solution used to disinfect the school. The child’s olfactory system also involves their ability to discriminate between odours and filter out those that they need to ignore. Some scents, such as smoke, need to be given immediate attention. Because we know how important sense of smell is for children and their learning ability, it’s important to understand the signs of sensory defensiveness.

There are differences and varying degrees of smell (olfactory) dysfunction. To learn how to identify this type of sensory issue, you may notice the following:

- Sensory Seeking with Smells

- Frequently tries to sniff people

- Excessively uses the sense of smell to identify a new object

- Seeks out strong odours

- Uses smell to interact with new places

Hypersensitivity of the Olfactory Sense:

- Objects to odours that most people ignore

- Tells others they smell bad

- Easily irritated by perfumes

- Determines if they like someone by the way they smell

- Bothered by cooking and cleaning smells

- Gags at the smell of certain food smells

- Acts out after the house is cleaned with strong chemicals

- Very sensitive to smell of smoke

- Exhibits increased sensitivity to smells and tastes

- Picky eater

Hyposensitivity of the Olfactory Sense:

- Never comments on how anything smells

- Is not bothered by strong odours

- Does not notice foul scents that others complain about

- May be unable to smell the food or meal

- Prone to eating or drinking non-edible or dangerous items because the initial smell factor does not inhibit or give warning signs

- Trouble identifying smells